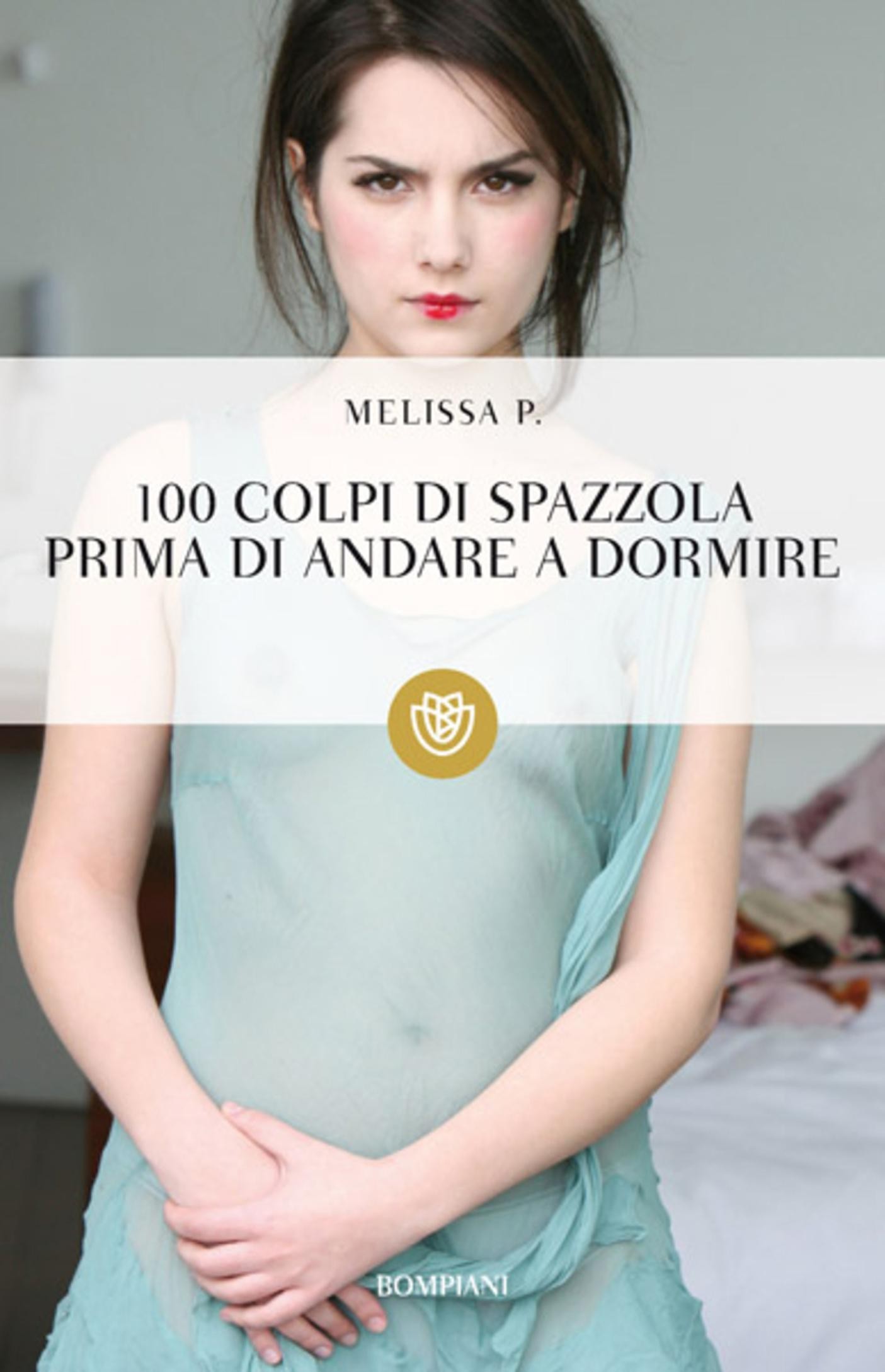

Melissa Panarello, now 18, attributes her sexual permissiveness to bad luck. “If you have bad luck, you start your sex life at a young age. It was my choice, but it’s also bad fate to find yourself in difficult situations at a young age.” Last July, her book, “One Hundred Strokes of the Hairbrush Before Going to Sleep,” was published in Italy. Written over a period of two years, it is the intimate journal of a Sicilian teenager who participated in group sex, sadomasochistic sex with a married man, sex involving every orifice of the body and sex in all types of erotic situations. It was published anonymously. The writer was identified only as Melissa P. The media dubbed her “the Sicilian Lolita,” she was interviewed only by phone or e-mail and appeared on television with her face concealed.

Melissa Panarello, now 18, attributes her sexual permissiveness to bad luck. “If you have bad luck, you start your sex life at a young age. It was my choice, but it’s also bad fate to find yourself in difficult situations at a young age.” Last July, her book, “One Hundred Strokes of the Hairbrush Before Going to Sleep,” was published in Italy. Written over a period of two years, it is the intimate journal of a Sicilian teenager who participated in group sex, sadomasochistic sex with a married man, sex involving every orifice of the body and sex in all types of erotic situations. It was published anonymously. The writer was identified only as Melissa P. The media dubbed her “the Sicilian Lolita,” she was interviewed only by phone or e-mail and appeared on television with her face concealed.Success was immediate. The book has thus far sold half-a-million copies in Italy (where the sale of 100,000 copies is considered a big success). Publishers from 16 other countries have also purchased the publishing rights to the book. Fazi Editore, the Italian publisher, also held negotiations with an Israeli publishing house, but nothing came of it in the end. A movie version is already in the works; the lead has been offered to actress Francesca Neri.

In early December, when Melissa P. turned 18, her identity was revealed. She is Melissa Panarello, a high-school student from the Sicilian town of Acicastello, near Catania. Her parents have a business selling clothing and shoes, and she has a younger sister. The family is well-off and respected. Her mother at first was hoping that her daughter’s experiences, as depicted in the book, were purely fictitious. When she understood that it was an authentic memoir, she took a deep breath and told the Italian media that she supports Melissa.

The Italian media have been skeptical of the book’s authenticity. “This book was not written by the person whose name is on it,” says Antonio Troiano, cultural affairs reporter for Corriere della Sera on the phone from Milan. “A bunch of people sat around a table and decided to publish a book in this style. They had a manuscript, but what came out in the end is something totally different. There were ghostwriters hiding behind Panarello. This isn’t a book, it’s a publishers’ project. It’s disgraceful that a publishing house that has published distinguished books did such a thing.” “That’s nonsense,” says Elido Fazi, owner of the press that published the book, from Rome. “We had a manuscript. We read it and loved it. The experiences of a young girl are described in a diary with tremendous candor. She described what she went through in a way that no one else had before. She has great talent. We thought the book had potential. We thought that people would read the book and talk about it.”

It’s clear to Panarello why the media are having a hard time believing that she wrote the book. “I broke a taboo in Italian society,” she says, on the phone from Rome, where she was staying last week. “Before my book, sex wasn’t talked about in this way. The book opened the floodgates of reality. I showed the hypocrisy of Italian society and therefore people are afraid of the book and are claiming that I didn’t write it.”

What hypocrisy did you expose?

Panarello: “Adult men having sex with young girls. The illusions of Internet sex.”

All of it happened to you?

“Some is real and some is fiction. Most of it is real”.

What part is fiction?

“All of the experiences are mine. I experienced all of these things. In the book, I described it all in a more dramatic way, but I didn’t make anything up”.

Weren’t you too young for such experiences?

“It’s how I felt. You can’t control that. That’s how I am, a girl with impulses and desires. Sexuality is a subjective thing that doesn’t depend on age. I could live this as a girl, as happened to me, or at age 40 or 50. It depends on you”.

What led you to have such an intensive sex life at age 15?

“I depended on these experiences in order to go on living. What I did made me feel alive”.

You didn’t feel humiliated or exploited?

“No. I was always aware of what I was doing and this awareness gave these actions dignity. I did it in a dignified way because I was aware of what I was doing. It doesn’t make any difference that I was just 15. You can have self-awareness at any age”.

What were you aware of?

“Of the reasons that made me do it. I wasn’t passive. I did it out of awareness. I wanted to be dependent on something. There are people who escape into alcohol. I escaped into sex. For me, it was an existential need. I was searching for something that would make me escape from my everyday life, I was searching for love. I was searching for myself”.

And what did you find?

“As I see it, the search is still continuing. I discovered things about myself that I didn’t know before. It helped me to grow. I saw that I’m not afraid to follow my desires. I put myself into certain situations in order to feel certain feelings. There were difficult experiences, but there wasn’t a single experience that was more difficult than the others. All of the experiences were difficult and important. It was an important experience. In the end, I was able to distinguish between true beauty and false fantasies. I saw the dark side of life and I came to understand the difference between true beauty and falsity”.

Your critics in Italy say that you’re a spoiled rich girl who was just so bored she didn’t know what to do with herself.

“A young girl of the age that I was doesn’t usually go looking for adventures, but for real experiences. For me, it wasn’t just having sex to pass the time, as older women do. I was searching for a true experience”.

Like a cancer

Panarello grew up in Acicastello, a Sicilian town of 19,000 people. In the book, she portrays her parents as not giving their elder daughter enough attention. Her father spends his free time watching television, and her mother spends most of her time at the gym. She grew up under difficult family circumstances, says Fazi, the publisher.

“My parents weren’t warm people,” says Panarello. “That doesn’t mean that they’re bad parents. They keep their distance, they don’t show emotion. But that doesn’t mean they didn’t love me”.

She told a reporter for the Italian magazine Panorama who wanted to write a profile of her that she didn’t leave the house much, avoided big crowds and generally kept to herself. In talking to Haaretz, she also described her life before the book’s publication as very normal, even dreary. She’d only left Italy once: “When I was a little girl, I went on a trip with my family to North Africa.” Her favorite writer is Anais Nin, and she likes movies, “as long as they’re dramatic and meaningful”.

She started writing when she was little, she says. An early story of hers has been making the rounds of the Internet in Italy. Called “The Right Moment,” it’s about a man and woman on a date. The language and style are childish: “They whispered their names at the same moment, their hearts pounded rapidly, his arms tightly embraced her shoulders. He whispered her name”.

At age 15, she met her first “man” – a 17-year-old – at a party. She told Panorama that she usually likes men who are 10 years older than her. She continued from there. She met several men through the Internet, on the computer in the garage of her parents’ home. She sat there for hours, surfing the Net and looking for thrills. Her parents knew nothing.

“They didn’t know what was happening with me. It’s very easy to hide things like this. Married women have affairs and they can hide it without a problem. I was also able to hide things. At that time, I was very involved in politics. I told my parents that I was going to political activities, to demonstrations, or to the opera”.

And in school?

“No one there knew anything. In the morning, I went to school like every other girl and in the evening I met men. Sometimes I would stay out until six in the morning and I had to be in school by 7:30. My girlfriends didn’t know anything either. I was completely alone with this. I didn’t tell anyone. I was afraid that other people would invade my territory and intrude on my space. I was afraid that they would disturb my intimacy, that they wouldn’t understand it”.

This fear didn’t hinder Panarello from keeping a diary and describing in it everything she experienced. “I wrote after hours of school. The need to put it in writing was very strong. I had to get it all out. It was like a cancer, I had to get it out of me. Some people see a therapist. I wrote”.

What did you want to get out of you?

“The spirits were haunting me”.

At the end of the book, after all the sexual adventures, Melissa P. finds a thoughtful, understanding man. That didn’t happen in reality. “I was searching for myself, searching for love. I didn’t feel loved. I didn’t love myself. I wasn’t in love and I wasn’t loved either.” But in recent weeks, she has developed a romance with Thomas Fazi, the son of her publisher. “They spent New Year’s Eve together,” says Elido Fazi. “But Thomas is very shy with women.” The experiences in the memoir take place over a period of two years. In reality, says Panarello, it all happened within just one year, at the end of which she submitted the manuscript to several publishers. “I wanted it to be published. It’s not embarrassing to me. Sex is not an embarrassing thing, though there are hypocritical people who are critical of the book.” Her parents tried to persuade her not to publish the book. As a minor, she needed their permission. “When they understood that the publisher was not trying to exploit me, they gave the green light”.

“We did not exploit her in any way,” asserts Fazi. Formerly a business reporter, he founded the small publishing house, Fazi Editore, eight years ago. Melissa’s book was published as part of an initiative to publish works by young Italian writers. “You exploit someone if he doesn’t know what’s happening. Melissa understands money. The book gave her self-confidence and publicity. If not for the book, she’d live out the rest of her life in a pretty miserable fashion”.

Yet Melissa says that the book hasn’t changed her life in any significant way.

“Maybe everything has become a little more intensive, and I also have more money, but meanwhile, I haven’t done anything with the money. Maybe I have more options now, but I still live with my parents in Acicastello. Life is pretty similar to how it was before”.

She has stopped attending her high school in Catania and is completing her studies on her own. Her close friends haven’t shied away from her.

“Maybe they discuss the book among themselves, but they haven’t said anything to me,” she says. “There’s no difference between me and them. We’re the same. We’ve just had different experiences. I imagine that they can relate to some of my experiences and can’t understand some of the others. They understand what I went through, but they don’t understand why I did it at such a young age”.

How did your little sister react?

“She didn’t know about what I was experiencing when it was happening. She discovered it all only when she read the book.

There was no point in hiding it from her. Now she’s proud of me”.

Extreme emotions While the book earned mixed reactions from young readers, the serious newspapers in Italy were united in their denunciation of the book. Reviewers criticized its inferior style, called it “pulp fiction,” said it was poorly written and portrayed fake experiences.

“Corriere della Sera didn’t write about the book in the culture section,” says Troiano. “As a literary work, the book is not important. If it merits attention at all, it’s as a social phenomenon. I find the language and quality of the book to be weak. There’s no story, no plot, no new and original idea, just a new Lolita trying to write an embarrassing book. To think of a 15-year-old girl doing all these things is terrible. She could be my daughter. And in the end, this isn’t Nabokov’s Lolita either. From the book `Lolita’ you remember the beauty of the writing. Anything can be written about as long as it’s written well. This book is not written well”.

Intellectuals aren’t wild about the book either. Alon Altaras, an Israeli writer who is a professor at the University of Siena, mockingly refers to it as “The Divine Comedy”: “In Italy, there hadn’t been a cheapening of literary taste,” he says. “Primo Levi is a best-seller. But when the prime minister is a person who makes unrestrained comments, the atmosphere is one of extreme emotions. Oriana Fallaci’s book with its overt hatred of Muslims, and a teenage girl’s book about wild sex, are what attract readers in such a wild atmosphere”.

Dr. Asher Sala of the department of Italian studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem says that on his last visit to Italy, two weeks ago, he saw copies of the book prominently displayed in large piles in bookstores, “but intellectual snobbery makes you refrain from touching it. The intellectuals are highly critical of the book. The tabloid press is praising [the author] for her courage, for the fact that she defied the taboos regarding teenage sex. And this is now the culmination of 100 years of Sicilian literature. The most important book of the early 20th century in Sicily was `Don Juan of Sicily,’ which dealt with the masculine side of sexuality. Sicilian literature has been overturned with this book”.

There are other views, of course. Panarello, who is currently writing a second book, published several short stories in Panorama. “She’s a good writer,” says Carlo Rossella, the editor of Panorama, in a phone call from Milan. “She knows how to write about sex, her descriptions are interesting, she has a special way of describing how a woman behaves, how a man behaves when he meets a young, pretty girl. She describes all of this in a very erotic manner. Yes, we’re Catholics, but sex is one thing and religion is another thing entirely. Italians don’t observe the commandment against adultery that well. This book sold because it’s a sex story of a young girl in Italy and was written in a very sexy and extraordinary way for Italian literature”.

Meanwhile, back home

One of the main reasons for the book’s success, says Fazi, is the fact that Panarello is Sicilian. “She gives a new perspective on Sicily. Up to now, people thought of Sicily as conservative. Sicily is a primitive place emotionally, but it is also very sexual and strong, like Melissa”.

Writers that have written about Sicily have emphasized Sicilian Puritanism. Leonardo Sciascia wrote that the family is the Sicilian state: The woman is wife and mother; the man is the ruler. Sexual relations before marriage can be punished with death. In the Italian subconscious, Sicily is a land that, on the one hand, is connected to the closed, traditional world, with strict sexual mores, says Sala, and on the other, is seen as a place with warm-hearted women who seek the most passionate experiences. “That’s why this book aroused so much curiosity”.

Panarello doesn’t see herself as a Sicilian writer. The heroine of her book has casual sex with men in their cars on the outskirts of Catania, but that’s the book’s only connection to Sicily. “Luigi Pirandello [author of “Six Characters in Search of an Author”] was a special Sicilian writer,” she says. “Today, Sicily is like any other place in Italy. These stories could have taken place anywhere else in the world, not only in Sicily”.

Having sold a half-million copies of her book and appeared on most of Italy’s major television programs, the young author says she isn’t worried about her image, in Acicastello or in general. “I live the way that I feel.” She believes the book has been an important experience for her. She would do it again in a minute, she says.

“I’ll never regret publishing the book. I want to study literature at the University of Rome. Maybe I’ll be a writer. Maybe in a few more years, once I’ve studied more and matured, I’ll feel embarrassed about the writing style, but I’ll never feel ashamed of what I did”.

Melissa Panarello. “Before my book, sex wasn’t talked about in this way. The book opened the floodgates of reality. I showed the hypocrisy of Italian society”.