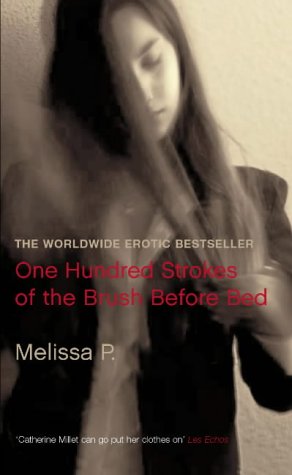

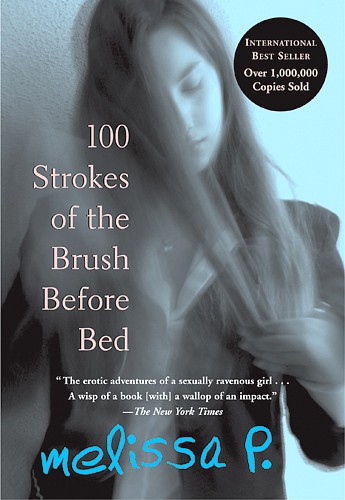

Contrary to what you might expect, 100 Strokes of the Brush Before Bed has almost nothing to do with hair-maintenance. The artfully obscured young thing on the cover of this book (she’s brushing a chunk of hair across her face) is the author and protagonist—or heroine, as she would no doubt prefer—of an X-rated fairy tale. Her name was Melissa P.; recently, she’s added a few more syllables to achieve Melissa Panarello. No longer artfully obscured, she’s regularly captured on camera spreading her milky thighs in a stiletto-boot-and-short-skirt ensemble, not quite concealing her knickers, or the modest teenage bosom spilling out of her Versace corset. Occasionally, she’s wearing a necklace with the words “Eat Me” on it, or smoking a cigarillo. Her doughy little face betrays little: She’s not frightened like a child, lascivious like a nymphomaniac or knowing like some media-savvy Lolita, although she’s been accused of being all three. Her face traffics in only one peculiarly modern commodity: adolescent ennui verging on disgust.

Contrary to what you might expect, 100 Strokes of the Brush Before Bed has almost nothing to do with hair-maintenance. The artfully obscured young thing on the cover of this book (she’s brushing a chunk of hair across her face) is the author and protagonist—or heroine, as she would no doubt prefer—of an X-rated fairy tale. Her name was Melissa P.; recently, she’s added a few more syllables to achieve Melissa Panarello. No longer artfully obscured, she’s regularly captured on camera spreading her milky thighs in a stiletto-boot-and-short-skirt ensemble, not quite concealing her knickers, or the modest teenage bosom spilling out of her Versace corset. Occasionally, she’s wearing a necklace with the words “Eat Me” on it, or smoking a cigarillo. Her doughy little face betrays little: She’s not frightened like a child, lascivious like a nymphomaniac or knowing like some media-savvy Lolita, although she’s been accused of being all three. Her face traffics in only one peculiarly modern commodity: adolescent ennui verging on disgust.

The erotic-chronicle epidemic has swept the globe, from France’s Catherine M. to our very own Jane J(uska), Japan’s Hitomi K(anehari) and Spain’s Valerie T(asso). Ms. Panarello is the Italian model, a porn principessa, the crucial difference being that Melissa P. is only 18, and was only 16 at the time of the events recounted in her book.

In Italy, her book has managed to sell nearly a million copies and remain on the best-seller list since its release last summer. She has become a national celebrity, appearing regularly on television and in magazines. Further book deals have been signed and there’s talk of feature films. In short, Melissa P. has become an icon of Italian youth culture.

But is her story emblematic?

The dull Sicilian suburb of Catania, where she scoots around on her scooter and lives above the mid-range clothing shop her parents own, is not enough to contain the worldly aspirations of Melissa P. She feels terribly misunderstood, particularly by her parents and teachers. In order to empower herself, young Meli starts keeping a diary and having oodles of sex: “At sixteen I’m mistress of my actions.” There’s plenty of fellatio; weekly sessions of gang rape, during which she wears over-knee stockings and five young men use their “lances” and “members” to “unload their whitish liquid on [her]”; a spot of S&M with an older man, whom she does with a dildo and leaves; a few ménages à trois; sex with a transsexual; sex with a lesbian; endless accounts of masturbation (she regularly “slips her fingers” into her “Secret”—in a moment of poetic magnificence, her widely shared “Secret” becomes her “foaming waves”); and an orgy.

And yet Meli is a dutiful girl. One hardly knows when she finds the time to do her homework, let alone brush her hair—100 strokes per night. Her mother taught her that to be a princess, one must brush away, and Meli really is a princess—though no one seems to recognize it.

Her insights are profound: “Who cares if it was right or wrong? The important thing is that we felt good, we lived deeply.” Who cares about AIDS or pregnancy? One wonders whether life is really so footloose and fancy-free in Sicily.

In fact, Meli feels dirty and ashamed after she strips off her over-knees and finds that she can’t quite get rid of that extracurricular stench: “I am dirty; only Love, if it exists, can cleanse me again.” But she hasn’t found Love despite all her carnal adventures. Near the end of her quest, she takes another peek at her tattered soul and finds that living “deeply” is not the key: “No, the fact is that nobody ever taught me how to express the love I kept hidden inside, concealed from everyone.” Then she meets a special boy, a liberator. Here she finds her voice and expresses her fervent gratitude: “[W]hen we are with you, in your arms, my panties and I are free of any impediment, any chains.” Melissa P. is not just a princess, but a bona fide wordsmith.

Forget the book—let’s take a look at how Meli became a best-selling author. She sent her diary to a few publishers via e-mail. Simone Caltabelotta, an editor with Fazi Editore (who is now—big surprise—Ms. Panarello’s boyfriend), read the manuscript and decided that with a little rewriting (or perhaps a great deal), it was publishable.

Sex sells. The book flew off the shelves in several European and Latin American countries; it’s been translated into most modern languages. Morgan Entrekin, president of Grove/Atlantic, has deemed it worthy of sharing sentence space with Henry Miller and D.H. Lawrence. Ms. Panarello—who, to judge by her facial expression, finds all this terribly dull and not at all scandalous—says she would like to see her book reverberate beyond sexual boundaries. It’s really about growing up in a dangerous world, she claims, though “the dangerous world” doesn’t get much play in between lances, members, secrets and brush strokes.

Ms. Panarello has been praised for her courage and honesty, but in fact her book is sentimental, coy and crass. It’s simultaneously clinical and euphemistic, because the author (or perhaps it’s her publisher) can’t decide what she wants. So what we get is a sequence of “ Penthouse Forum”–style fantasies mixed up with a whimper of adolescent angst and a handful of fairy dust.